Before I ever held a book, I held a worn-out komiks. My yaya rented it from the neighborhood sari-sari store. The pages were soft from use; the cover was held by tape. I couldn’t fully read yet, but I followed the images, looking at the movement, faces, and sound effects.

Back then, komiks were everywhere. People read them while eating, riding, or resting. Even with missing or dog-eared pages, they kept circulating. For kids like me, they were part of the day.

I didn’t know the artists then, only the worlds they created. Francisco V. Coching’s pages were cinematic. Mars Ravelo’s Darna, Captain Barbell, and Lastikman taught us strength and fairness.

Komiks reflected everyday life. Larry Alcala’s Slice of Life found humor in daily routines. From old clippings, we discovered Mauro Malang Santos’s Kosme the Cop, a tough officer submissive to his brusque wife. Though later known for painting, Malang helped shape the tone of local newspaper comics. Coching and Alcala were later named National Artists, affirming the role of komiks in Filipino culture.

In the 1980s, Pilipino Funny Komiks became part of my weekly routine. My friends and I passed each issue around. At home, while my dad read the main sections of the paper, I turned to Ikabod Bubwit by Nonoy Marcelo and Pupung by Tonton Young.

Komiks followed us to school. Teachers used them to explain science, history, and civics. We read in libraries, canteens, under trees, and between classes. In Catholic school, Gospel Komiks was part of Christian Living class.

By high school, I was collecting DC and Marvel titles. Still, I read Pugad Baboy in the paper. Pol Medina Jr.’s characters spoke like us. They dealt with traffic, politics, family, and work. Polgas, the talking dog, said what others wouldn’t. Eventually, I started buying the collected editions. Pugad Baboy helped my generation laugh through everyday struggles.

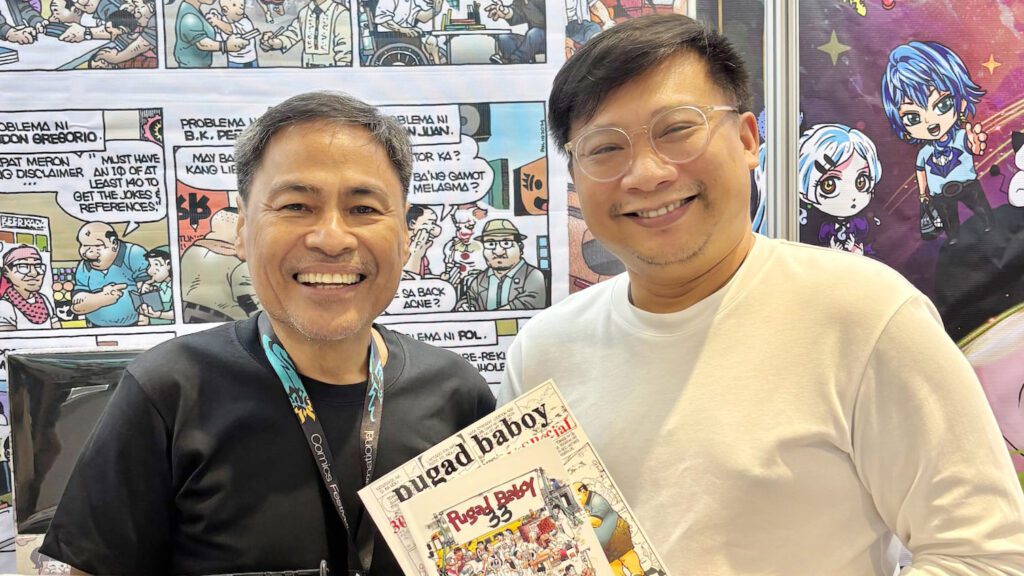

That connection resurfaced this July at the Philippine International Comics Festival at SM Megamall. Medina launched the 34th anniversary issue of Pugad Baboy. New local titles appeared alongside comics from Palestine, Germany, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and South Korea. The hall filled with artists, readers, and fans.

Among my haul was Drawn from the Islands, an anthology from the Samahang Kartunista ng Pilipinas. It offered fresh takes on Filipino folklore for young readers. Marco Bermejo’s Ang Alamat ng Bulkang Mayon, Amiel Rufo’s Kapwa, Maria Makiling, and Chong Ardivilla’s Maria Cacao stood out for their storytelling and visual style.

New voices are emerging. Kevin Eric Raymundo’s Tarantadong Kalbo delivers sharp commentary through minimalist panels for digital platforms. Arli Pagaduan’s Cat Cafeteria tells a quiet story of care and kinship. It reads like a guide to building cat communities. Lucas Lacorte’s Watchdog of Manila draws a surreal and eerie version of the city. He is a young creator to watch.

Today, Filipino artists reach readers worldwide. Leinil Yu, who illustrates for Marvel’s X-Men and Avengers, brings local craft to international comics.

In a digital age where images are instantly generated, komiks remain intentional. Each panel requires a decision about what to draw, what to say, and what to leave out. That way of seeing shaped how we read the world. What began with one worn komiks became a habit of paying attention, one panel at a time.